Culture of Uzbekistan : history, people, clothing…

People

Ethnic groups

The current population of Uzbekistan is 33.5 million. Seventy-five to 80 percent are Uzbek, though many of these were originally from other ethnic groups. Russians and Tajiks are each 5 percent, Karakalpaks 2 percent, and other nationalities the remainder. From 1989 to 1996, five hundred thousand more people emigrated than immigrated; most of the emigrants were educated. Of the more than one million people who have left, essentially all were non-Uzbek. Cities like Andijan and Fergana, whose populations had been only half Uzbek, are now virtually entirely Uzbek. In 1990, 600,000 Germans lived in Uzbekistan; 95 percent have left. In 1990, 260,000 Jews lived in Uzbekistan; 80 percent have left.

Languages

The Uzbeks speak a language belonging to the southeastern, or Chagatai (Turki), branch of the Turkic language group. Karakalpak, a distantly related Turkic language, enjoys official status alongside Uzbek in Karakalpakstan, where it is spoken by about half a million people. About one-seventh of the population of Uzbekistan speaks Russian.

Religions

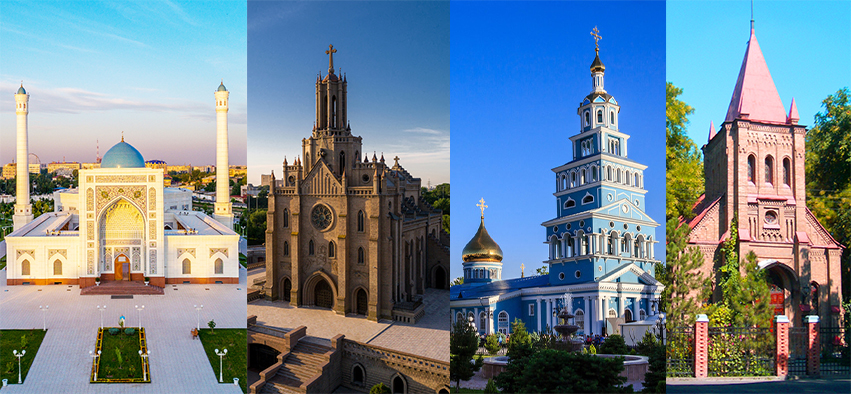

The Uzbeks are Sunni Muslims, and they are considered to be among the most devout Muslims in all of Central Asia. Thus, about three-fourths of the population is Muslim. Slightly less than one-tenth of the population is Eastern Orthodox Christian, and the remainder of the people consider themselves nonreligious or follow other religions.

Settlement patterns

Most of the population lives in the eastern half of the country. Heavily populated oases and foothill basins are covered with an extensive network of canals intersecting fields, orchards, and vineyards. The fertile Fergana Valley in the extreme east, the most populous area in Central Asia, supports both old and new cities and towns and traditional rural settlements. Much of Karkalpakstan, in the west, is under threat of depopulation caused by the environmental poisoning of the Aral Sea area.

Roughly half of the population of Uzbekistan lives in urban areas; the urban population has a disproportionately high number of non-Uzbeks. Slavic peoples—Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians—held a large proportion of administrative positions. In the late 1980s and early ’90s, many Russians and smaller numbers of Jews emigrated from Uzbekistan and other Central Asian states, changing the ethnic balance and employment patterns in the region.

The cities of Samarkand, Bukhara, and Tashkent have histories that extend back to ancient times. Andijon (Andizhan), Khiva, and Qŭqon (Kokand) also have served the region as cultural, political, and trade centres for centuries. Soviet-era architects purposely laid out some newer towns, including Chirchiq, Angren, Bekobod, and Nawoiy (Navoi), close to rich mineral and energy resources. Soviet planners also sited Yangiyul, Guliston, and Yangiyer in areas that produce and process cotton and fruit.

Good public housing continued to be in short supply well into the late 20th century, despite large outlays by the government in this sector. As late as the 1990s, private ownership of urban housing had not become common in Uzbekistan, though suburban plots around Tashkent and other cities became available in large numbers for citizens able to erect their own houses—usually simple, low structures, like those in the past, built around courtyards planted with fruit trees and gardens open to the skies but closed off from the streets.

Demographic trends

Uzbekistan’s population remains youthful in comparison with those of the western parts of the former Soviet Union, though the population aged slightly and steadily over the decades following its independence. Nearly half the population is in the age range of 25–54. This age structure results from the high birth rate after independence: of all the former Soviet republics, Uzbekistan had the greatest number of mothers with 10 or more living children under the age of 20. The birth rate has since decreased.